A comic novel about “mass mansionization” spoofs the reverse snobbery of people who delight in crumbling old dwellings.

By Allan Fallow

In the opening pages of White Elephant, REALTOR® Nina Strauss is driving her two exhausted clients, Grant and Suzanne Davenport-Gardner, toward her leafy hometown of Willard Park, Maryland. “It’s on the expensive side—I won’t lie,” Nina alerts them. “But you won’t be sorry. It’s where I live. It’s idyllic. I don’t show it to just anyone.”

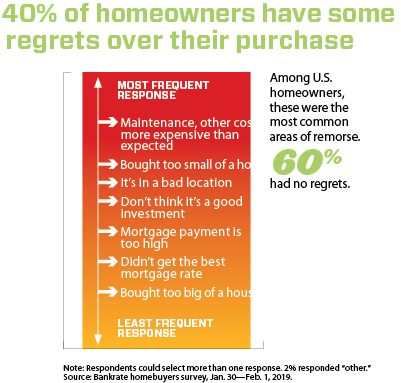

“It” is a circa-1918 Sears Modern Home, “a sweet two-bedroom bungalow with a porch and a second-floor balcony. The house originally sold for $1,172.” Grant and Suzanne purchase the place, but buyers’ remorse soon bedevils them.

The reason for their regret struck this reader as absurd: What homeowner would rip out drywall and siding because they mistook marijuana smoke for “toxic black mold”? But debut novelist Julie Langsdorf uses that plot device to chase Grant and Suzanne from their wrecked home and into successive sojourns with two families waging a war for the soul of Willard Park.

Homey vs. progressive

Representing the preservationist urge are Ted and Allison Miller. He’s the schlubby editor of an alumni magazine, eager to keep the town “the homey way it had been when he and [twin brother] Terrance were growing up.” She’s a hot-blooded amateur photographer, bent on capturing local quirks for the coffee-table book she hopes to publish, Willard Park: An American Dream.

Town residents for 14 years now, the Millers have a retro-chic view of real estate: “A sense of home and community,” Allison muses. “That was what mattered—not whether you had a second bathroom. She and Ted were in agreement about that.” Their daughter, Jillian, came along a year after the Millers moved into their 1910 two-bedroom home, which is “so old that Sears hadn’t even started naming the models yet.”

Advancing a far more progressive view, meanwhile, are Nick and Kaye Cox. He’s a tall, perennially cash-strapped and dangerously good-looking developer. “There was something brutal about him,” thinks Allison, “but it wasn’t unattractive”—who dubs the town’s modest bungalows “obsolete.” She’s an overeager blonde, “toes polished in her high-heeled sandals,” whom Allison deems “a little [too] highlighted and made up for Willard Park.”

Relative newcomers (Nick’s been chased out of Beaufort, South Carolina, by some pesky lawsuits and building-code violations), the Coxes will likely never fit in with the “old granola heads” who rule Willard Park:

The neighbors might have forgiven them the sin of bad taste with time, but as the months wore on, the Coxes continued to disobey the unspoken rules of the neighborhood. They didn’t compost. They had pesticides sprayed on their lawn. They didn’t join Friends of the Willard Park Children’s Library. They didn’t even recycle. … The Coxes were like foreign visitors who had not read up on the local customs.

McMansion sandwich

Nick has committed an unforgivable offense by building a residential monstrosity on either side of the Millers’ diminutive dwelling—wedged between McMansions. To the Millers’ right now rises the “faux stone castle” occupied by the Coxes, its turrets and spires painted gold—or is that gold leaf? “The inhabitants of an entire ZIP code could have lived in it comfortably,” Allison fumes.

And to their left stands the four-story abomination that gives the novel its name, soaring higher than any other home in town and casting a literal and metaphoric shadow over the Millers’ humble abode: “It was painted bright white and had been sitting on the market for months—hence the nickname, which Ted had come up with himself. It had caught on, he’d been pleased to learn, but that was the only thing about it that pleased him.”

Ted would be even less pleased to learn how his wife, Allison, and his archrival, Nick Cox, have been secretly compensating for the “sexual sabbatical” Ted’s opted to take. Isn’t it bad enough that Nick has rashly cut down trees—including one planted in Jillian’s honor the year of her birth—to expose the White Elephant to prospective buyers’ eyes? “Let’s hope he doesn’t start a trend,” frets Nina. “The trees make this town. Honestly. They’re half its charm. Take down the trees and I’m going to need a new place to hang my shingle.”

Sorry, Nina: Soon enough copycat lumberjacks are felling trees (including the town Tannenbaum) all over Willard Park—to say nothing of dumping the town-hall garbage on village lawns, defacing stop signs with the words clinging to the past, and spray-painting pro-growth slogans on playground slides.

As Willard Park becomes more Peyton Place than Bedford Falls, a building moratorium is enacted and residents’ shameful secrets mysteriously begin to appear on the bulletin board of the local café. Langsdorf unwisely shoehorns in a subplot about a romantic rivalry between Jillian and 13-year-old Lindsay Cox. (Of course Nick’s daughter would be a Mean Girl!) Still, it’s a compelling enough thread to make you wish the ultimately lumbering White Elephant had been written as a young-adult novel instead. That way Langsdorf could have spent more time developing her favorite character—and mine:

[Jillian] distracted herself by naming the Sears houses she could see: the Glyndon, the Hazelton. If she named all of the house models correctly on her way to school, she would have an okay day. … It was weird to think that in olden times you could order a house as a kit from a catalog. She imagined what would happen if you could order a house online. It would probably arrive by drone two days later, possibly crushing an evil witch or two when it landed.