The man who landed a rover on Mars has learned a thing or two along the way about creativity. He shares it here.

Reviewed by Allan Fallow

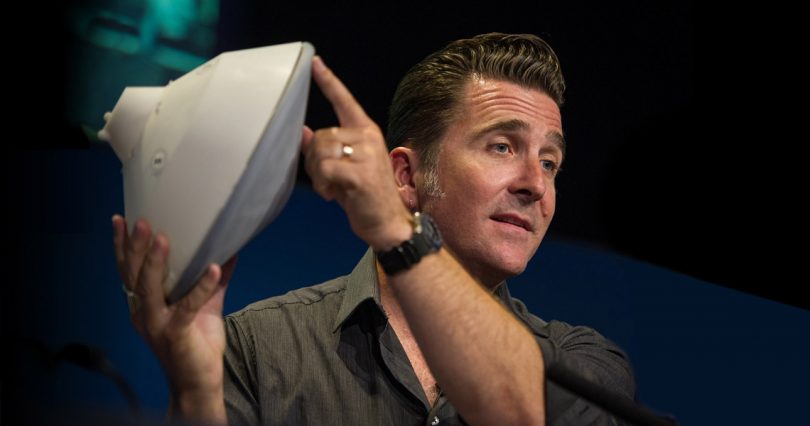

Adam Steltzner is the Jet Propulsion Laboratory engineer who helped mastermind the Sky Crane landing system that gently deposited the Curiosity rover on Mars in August 2012. But don’t expect his memoir to be wall-to-wall rocket science. The bulk of The Right Kind of Crazy concerns itself with how to build, lead or simply contribute to a winning team effort.

Despite his status as a media darling—his Elvis haircut and ear piercings led NPR to dub him a “rock-and-roll” engineer—Steltzner stays focused here on the true stars of planetary exploration: people. Regularly reminding us that “engineers aren’t robots,” he takes pains to humanize the scientific process.

When his team discovers a mission-jeopardizing navigation error just 72 hours before their spacecraft touches down on Mars, for example, Steltzner calmly assembles the “tiger team” needed to correct the craft’s center of navigation by three inches. “Had we just screwed the pooch,” Steltzner wonders, “or had we averted an ‘O-ring moment’ and saved the entire mission?” He uses the episode to ruminate on uncertain outcomes and unseen paths, and to explain why “an appreciation of the limits of your understanding [is] paramount … whether you are engineers building a spacecraft or developers working on the next big iPhone app.”

Overcoming Fear

Steltzner claims he wrote The Right Kind of Crazy to furnish “a fresh perspective on how leaders can successfully engage smart people to build challenging, high-stakes, innovative projects.” Yet rarely were the words “successful” or “engaging” applied to the youthful Steltzner. “I was not one of the math geniuses who carried a briefcase and won physics prizes in high school,” the author confesses. “My only good subject was theater, and instead of studying, I smoked pot, rode mountain bikes, chased girls and played gigs with my band. I had no real ambitions except perhaps to magically become Elvis Costello or Joe Jackson.”

Steltzner may have come by his flair for the dramatic—which was essential in persuading NASA chief Mike Griffin to approve an unorthodox landing system for the Mars rover—from his mother, a former WAAC and beatnik who managed nightclubs in San Francisco and dated “influential female artists.”

His father’s legacy is cloudier. Perhaps because Steltzner senior was an heir to the Schilling spice fortune, “he never showed much interest in earning a living,” his son reflects. “Work meant struggle, struggle meant the possibility of failure, and failure was simply unacceptable.” As the family fortune trickled away, the father descended into denial, despair and drink—and the son rebelled by becoming “a human projectile”:

“At a very early age, I pursued every form of physical recklessness, from skateboarding in traffic to biking down steep mountain roads at racecar speeds. I was the kid who climbed every fence and leapt off every ledge. In retrospect, I think I was trying to escape the fear that seemed to cage my father, or to suspend it via an act of will and perhaps grab on to something real and true.”

But what the future JPL scientist often grabbed onto was thin air, breaking 32 bones by the time he barely graduated from high school in Marin County, California. Property owners smeared axle grease on catwalks and fences to dissuade him. But that only sharpened the appeal of tightrope-walking a 25-foot-high roofline peak. “Get off the roof, Adam!” became a neighborhood refrain—as did “Hello again, Adam” every time he was readmitted to the local ER.

Good thing Steltzner survived his reckless adolescence, for The Right Kind of Crazy is a handy manual for those in any field who want to unkink group dynamics, know when to suggest and when to insist, or simply get at the truth. His approach to an engineering problem will be familiar to any manager who has ever painted himself into a corner: “You have to stay calm, hold on to the doubt, listen to the problem, and keep thinking of solutions while avoiding the mind-locking panic that you won’t find one in time.” (Imagine your product-debut date being dictated by celestial mechanics!)

Embracing Curiosity

Steltzner details his recipe for getting ahead in the chapter titled “Self-Authorization,” ruminating on the responsibility that every member of a team owes the collective effort. He then pushes his definition of individual contributions even further: “You need to believe you have the answer, and you need to give it to the team, even if you only think you have the answer. It is a form of leadership” (which Steltzner later calls both “a sign of service” and “a gift to the group”).

Also worth a read is Steltzner’s take on bad vs. good decision making: In the fear-based version, the sheer suspense of an open question pressures an individual or group to embrace an imperfect solution; in its curiosity-based counterpart, we revel in that open question, pulling it apart and staving off a decision until the best one emerges.

If all that sounds hifalutin, consider how down to Earth this orbital scientist can be when it comes to the people we work with day in and day out. Indeed, it’s hard to imagine a more enlightened human-resource philosophy than the one this hard-boiled egghead espouses, almost in spite of himself: “Sometimes you can’t get all the way to loving the whole person, but maybe you can love the goofy way they show up in a bike helmet, or the way they have those cat pictures all over their work space, or how they can’t help dreaming of solutions that appear off topic. Oddly enough, in time the love actually happens.”

Now that’s what I call the right kind of crazy.

You Might Also Like…