Fed up with the abstractions of her desk job as a wordsmith, a young journalist reinvents herself as a woodsmith.

Reviewed by Allan Fallow

“Carpenter’s Assistant” read the posting in the “Etc.” category of the Craigslist job section. “Women strongly encouraged to apply.”

Nina MacLaughlin was intrigued. The young woman had recently made several seismic changes in her life, quitting her job (as managing editor of the Boston Phoenix website), breaking up with a boyfriend and moving out of her apartment. Now, eager to put some distance between herself and “the echo chamber of the Internet,” MacLaughlin replied to the ad — and was astonished to learn, when the hiring carpenter named Mary responded, that more than 300 hopefuls had likewise answered the notice in just the first 18 hours of its posting. “Sign of the times,” Mary laconically observed. After giving MacLaughlin a half-day tryout, Mary signed her on, agreeing to teach her a craft the author hoped would satisfy her urge “to put my brain where my hands were.”

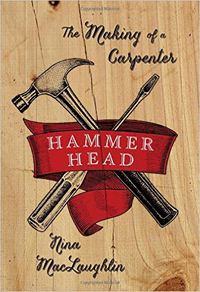

Five years later, MacLaughlin is still swinging a hammer, having built walls, decks, bookcases and a chase — a tall, narrow, three-sided box that hides pipes from view. Along the way she also constructed this book, a granular, often meditative account of her on-the-job experiences in the land of 2-by-4s, kitchen counters and concrete dust. Reminiscent of both Tracy Kidder’s House and Matthew Crawford’s Shop Class as Soulcraft, MacLaughlin’s Hammer Head is about much more than sistering joists and toenailing studs: It gets at the nature of transformations, both physical (board to shelf) and personal (writer to carpenter), as well as answering the ne plus ultra question, “How do we decide what’s right for our own lives?” (Hey, what did you think would happen when a former classics major strapped on a tool belt?)

DRIVING IT HOME

Much of the book’s charm stems from the naïve abandon with which MacLaughlin throws herself into every assignment that comes her way, whether she knows how to accomplish it or not. Handed a crowbar by Mary and instructed to, “Take up the stair treads down to the basement” inside a stately old home the two are renovating near Harvard Square, MacLaughlin dives right in, “hop[ing] that what I was about to do was what Mary had in mind.” Happily, she’s delighted with the results:

I jammed the [crow]bar … underneath the tread of the top stair. I pressed up, heaved and ho’d, and felt the board peel up and pop under my efforts with a wailing sound of nail releasing its hold on wood. I couldn’t believe the force of the bar. I popped off the top of one stair, then another, ratty pieces of dark wood, faded gray and splintery where feet have landed and landed, up and down. I grunted and sweat.

Having demolished nearly the entire staircase, MacLaughlin stands at the bottom and triumphantly calls up to her boss, “The crowbar’s amazing. I feel like a superhero.”

“Good for you,” Mary replies. “Next time, start at the bottom and work your way up.”

After burning out in her previous job, where she had been reduced to editing such brainless click-bait as “The 100 Unsexiest Men,” MacLaughlin takes righteous pride in turning out items of true substance. Her enthusiasm is innocent and infectious. She and Mary build a back deck on a house in Somerville in one short week, whereupon the author wants to stress-test their handiwork: “Can I jump on it?” she asks Mary.

“Knock yourself out,” comes the answer. “So I jumped hard on the platform,” MacLaughlin writes. “Solid. Nothing shook. It took my weight.” She and Mary had hardly completed the pyramids or the Parthenon, she allows, but they had created “a way to get from a door down to the ground, a passage and a place to pause, to pile groceries, to stomp snow off boots on the way inside. What a thing!”

TOUGH AS NAILS

When she’s not marveling at the transformation of one object (or occupation) into another, MacLaughlin gives us gritty character sketches of the people — overwhelmingly men — she comes in contact with on various job sites. None of the male tradesmen, however, are drawn as affectionately as Mary, a self-described “43-year-old married lesbian with a 10-year-old daughter.” “Petite would be a word for her if she didn’t carry herself with the force and presence of someone much larger,” MacLaughlin observes, “if she weren’t able to hoist 80-pound bags of cement onto her shoulder as though she were lifting a sack of pine needles.” Raking her hands through her short, wiry, salt-and-pepper hair, Mary takes shape in these pages as Yoda to the author’s Luke, right down to such “Use the force”-style pronouncements as “Be smarter than the tools,” “Let the materials tell you which way they want to go” and “Finesse, girlfriend.” Hammer Head is dedicated to Mary.

Although MacLaughlin was lucky to find such a patient female mentor, the gender realities of her adopted profession sound pretty unforgiving. Whereas the percentage of women dentists rose from 1.9 percent in 1972 to 30.5 percent in 2009, and the ranks of women mail carriers swelled from 6.7 percent to 35 percent in the same time frame, female carpenters increased from a downright deplorable 0.5 percent to a merely negligible 1.6 percent. “The fact is,” MacLaughlin concludes, “carpentry is men’s work. Which is to say, carpentry is work that is statistically done by men.” (Indeed, of all the occupations the U.S. Census Bureau lists in its 2011 survey, construction and extraction are the most out of balance in terms of gender.)

In a touching coda, MacLaughlin capitalizes on everything she’s learned from Mary to custom-build a set of bookcases flanking the fireplace in her father’s new home. Despite her misgivings (What if I can’t translate what I know to the wood?), she completes the job — and recognizes that the pieces of her life may be finally fitting together, too: Placing her carpenter’s level on one of the finished shelves, MacLaughlin “watched the bubble shift and settle. It wasn’t right there in the middle. But it was good enough.”

As in wood, Hammer Head reminds us, so in life.