How a pillar of American leisure—the Parker Brothers board game Monopoly—lost its stranglehold on its own creation myth.

Reviewed by Allan Fallow

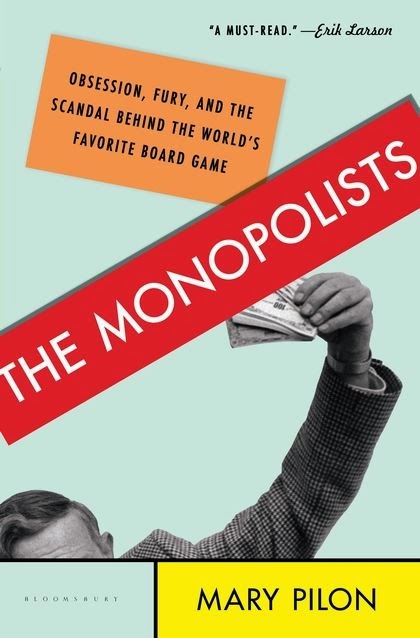

Vengeance — of the board-game variety — is pursued and ultimately achieved in The Monopolists: Obsession, Fury, and the Scandal Behind the World’s Favorite Board Game. In it, New York Times sports reporter Mary Pilon tells how a Berkeley professor triumphed over a corporate giant, Parker Brothers, in his quest to market Anti-Monopoly, the game he invented during the oil crisis of 1973 to teach his young sons the evils of OPEC. It’s a tangled tale of creative attribution and intellectual property theft that stretches from gilded-age America in the 1890s to the steps of the Supreme Court in 1983.

According to the creation story tucked inside every box of Monopoly that Parker Brothers sold for decades starting in 1935, unemployed Philadelphia salesman Charles Darrow had singlehandedly invented the “world’s favorite board game” in his basement during the Great Depression. The “scandal” in the book’s subtitle is that Monopoly is in fact based on the trust-busting “Landlord’s Game,” patented by a freethinking young woman in 1904. But when Parker Brothers acquired Darrow’s version of the game, Darrow assured the company that Monopoly was “my brain child” and “my idea.” That claim, writes Pilon, “was somewhere between a stretch of the facts and a lie.”

Lizzie Magie, Monopoly’s overlooked originator, was working as a typist in Washington, D.C., when she came up with the idea for the Landlord’s Game in the early 1900s. She intended it less as a pastime than a parable — one designed to promote the economic theories of Henry George, a charismatic politician of the 1880s and 90s who urged freedom from taxation on all goods except a “single tax” on land.

Play the Market

In an age when Andrew Carnegie had cornered the steel market and John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Trust controlled nearly 90 percent of the country’s oil, George attracted a following for insisting that “Land was not meant to be seized, bought, sold, traded or parceled up into city blocks where people were forced to pay exorbitant rents.” Good thing, then, that he died in 1897: George would have been aghast to see his ideals perverted in a board game sweeping the nation 40 years later.

Lizzie Magie was both a maverick and a dynamo. Not only did she save enough money on her own to buy a house and several acres in Prince George’s County, Maryland, but in 1893 she applied for — and would ultimately be granted — a patent for a gadget that simplified feeding paper into a typewriter. Her Landlord’s Game, patented in 1904 and again in 1924, was designed to be played on a square board divided into 40 spaces, 10 to a side. It featured “play money and deeds and properties that could be bought and sold.” In other echoes of the modern game, there was a railroad space midpoint on each side, plus corner spaces labeled “Go to Jail” and “Public Park” (the obvious forerunner to “Free Parking”). Even a proto-“Go” space could be discerned beneath its Georgist motto: “Labor upon Mother Earth produces wages.” Magie hoped the game would teach players “the gross injustice of our present land system.”

Magie’s anti-agglomeration game was a hit with progressives, making its way from the utopian society known as the Village of Arden in Delaware in the early 1900s to a Quaker enclave in, of all places, booming Atlantic City in the mid-1920s. Drawn to the seaside resort from crowded Philadelphia, the Quakers hoped to establish “a healthy, fresh-air community, complete with modest accommodations and prayer lodges.” Ironically, some of the city’s most glitteringly elegant hotels would come to be owned by simplicity-loving Quakers.

At the home of Cyril and Ruth Harvey, teachers at the Atlantic City Friends School — funded by wealthy Quaker hoteliers — one aspect of the game caused real estate to collide with religion: “[M]any around the Harveys’ table who held silence to be a tenant of their faith were against allowing [noisy] auctioneering [of properties] to be part of the game.”

But with the game’s rules yet to be codified, a real estate agent who was a friend of the Harveys contributed a couple of key modifications: Jesse Raiford experimented with applying color sequences to the board, “finally deciding to divide the properties into groups of three.” And because Raiford’s work had made him “closely familiar” with Atlantic City property values, he also felt confident affixing prices to the game board.

By the time a copy of this popular “monopoly game” fell into Charles Darrow’s hands in 1932, the Depression had thrown him out of work. Tragedy struck again when a bout of untreated scarlet fever left his younger son, Dickie, mentally disabled; the boy would require expensive care for the rest of his life.

Guarding a Monopoly

Although Pilon rightfully makes Darrow out to be the villain of this saga — he began publishing the game on his own, the board emblazoned with the unsubstantiated claim “COPYRIGHT 1933 CHAS. B. DARROW” — it’s hard to assail his motives. Yes, Darrow hoodwinked Parker Brothers. But the game’s overnight success — it sold 278,000 units in 1935, 1.75 million the next year— enabled the Darrows to house Dickie at a facility noted for its humane treatment of the mentally impaired.

The endgame of The Monopolists re-creates a David-and-Goliath struggle, with Parker Brothers waging a 50-year war to guard its monopoly over Monopoly. Indeed, had the company not sent a cease-and-desist letter in 1974 to Ralph Anspach, the economics professor who would sell 74,000 copies of his homemade Anti-Monopoly game that year and 200,000 the next, Monopoly’s socialist roots might never have been exposed: Anspach dug them up during his decade-long legal battle with Parker Brothers, which cost him his marriage but won him a seven-figure settlement from the firm.

Ralph Anspach never deluded himself that Monopoly is “just a game,” but there is circular justice: he was finally able to pass “Go” and collect a bit more than $200.