It’s time to put curiosity where it belongs, says a Hollywood producer—right up there with creativity and innovation.

Reviewed by Allan Fallow

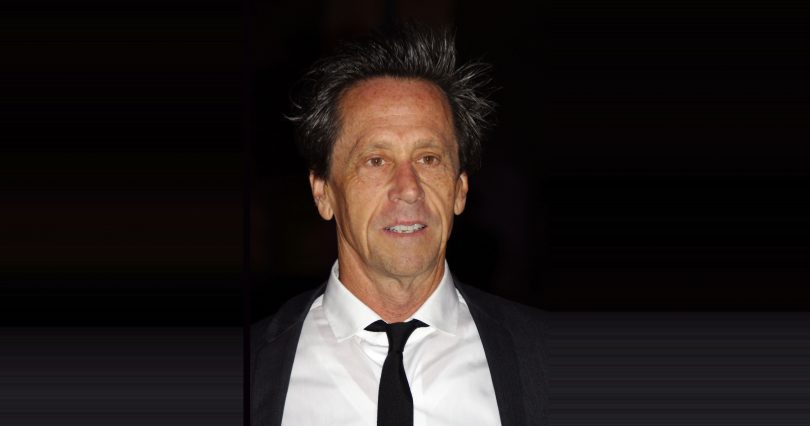

Oh, to have been a fly on the wall of Brian Grazer’s office! Over the last 35 years or so, Ron Howard’s producing partner (Splash, Friday Night Lights, A Beautiful Mind) has held informal “curiosity conversations” with 466 luminaries from all walks of life — “people immersed in everything from particle physics to etiquette,” as Grazer puts it in his new business manual-cum-memoir, A Curious Mind: The Secret to a Bigger Life. His hunger to discover what makes other people tick has introduced Grazer to everyone from Muhammad Ali to Steve Wozniak.

It has also landed him in a few interesting predicaments:

He shared a bowl of ice cream with Princess Diana at the 1995 London premiere of his Apollo 13.

He got cut off at the knees by Mrs. Isaac Asimov: “You clearly don’t know my husband’s work well enough to have this conversation,” Janet Asimov curtly informed Grazer 10 minutes after they met for drinks in 1986. “This is a waste of his time. We’re leaving. C’mon, Isaac.”

And in 2004 he got put in a headlock by Norman Mailer in the lobby of the Royalton Hotel in midtown Manhattan. (Grazer had asked Mailer to describe how one boxer had thrown another out of the ring, and Mailer decided to demonstrate.) “With [Mailer’s] arms wrapped around my head,” Grazer recalls, “it was clear how strong he was. It was slightly embarrassing. I didn’t want to struggle. But I also wasn’t quite sure what would happen next. How long would Norman keep me in the headlock? It lasted long enough to leave a strong impression.”

Don’t Quote Me on That

A Curious Mind leaves a strong impression, too — but it may not be the one that Grazer and co-author Charles (The Wal-Mart Effect) Fishman intended. In a book stuffed with more celebrities than a Vanity Fair after-party, the reader has every right to expect a few verbatim pearls from the lips of Grazer’s interlocutors. Yet one of the few direct quotes I could find — from a pajama-clad Oprah — is hardly illuminating: “I’m always trying to solve life myself,” she told Grazer over a breakfast of huevos rancheros in the courtyard of L.A.’s Bel-Air Hotel in 2007.

Grazer’s reason for this maddening mushiness emerges from one of the book’s many appendices, this one titled “How to Have a Curiosity Conversation.” To start a person talking about himself, the author recommends, don’t write anything down: “The goal is a good conversation,” he advises. “Taking notes might just make someone uncomfortable.” The journalist in me — the compulsive stenographer who once interviewed Jane Lynch with two recorders running — struggled not to throw A Curious Mind across the room when I read this bogus guidance.

But who cares if we’ll never know what Linda Ronstadt may have said to Dr. Jonas Salk when they met (along with George Lucas, Sydney Pollack, and Betty Edwards) for “a daylong conversation” in the living room of Grazer’s Malibu house in 1984? For all its stargazing, A Curious Mind is a business tome, not a Tinseltown tell-all, and I suspect REALTORSи will derive some powerful lessons from Grazer’s ruminations on 1) the value of “managing by asking around” and 2) the use of curiosity to overcome an initial “No.”

Grazer is not a natural manager, he reveals in these pages. (“I don’t like to boss people around.”) He is uncomfortable issuing direct orders, yet as co-chairman of Imagine Entertainment, he is responsible for seeing that hundreds of employees do their jobs on a daily basis. How does he cope with that burden? By asking questions — which Grazer calls “an underappreciated management tool” — of the people who work for him.

But where’s the productivity payoff in that? For starters, asking questions engenders engagement and commitment in your co-workers — but, as Grazer allows, the effect is subtle. Let’s listen to him explain it (ignoring our suspicions that his “hypothetical” sounds like an “actual” from the Hollywood trenches):

Let’s say you have a movie that’s in trouble. You ask the executive responsible for moving that movie along what her plan is. You’re doing two things just by asking the question: You’re making it clear that she should have a plan, and you’re making it clear that she is in charge of that plan. The question itself implies both the responsibility for the problem and the authority to come up with the solution.

Getting to Yes

The portion of A Curious Mind dedicated to “beating the ‘No’” — it’s Chapter 4, if you’re pressed for time — should be required reading for salespeople. Hollywood is the land of “No,” writes Grazer — so much so that those famous white letters teetering precariously above the Hollywood Hills should spell out N-O-N-O-N-O-N-O! But by using curiosity to fight fear and instill confidence, the author claims, he has learned how to ask enough questions to pinpoint precisely what people are saying “No” to. (In this regard, he enthuses, curiosity functions as “a quiet kind of power … a cumulative power … a power for real people.”)

As an object lesson in adaptation to sales resistance, he traces the seven-year journey of his first mega-hit, Splash, from script page to multiplex screen. Pitched as a movie about a mermaid, the picture went nowhere. With a little probing, however, Grazer ascertained that studio executives were saying no to the mermaid herself, so he recontextualized (his emphasis) the film as a love story between a man and a woman (who just happens to be a mermaid) with a little comedy thrown in. “Same idea,” he sums up this strategy, “different framework.”

Splash became a huge hit. It launched the careers of Tom Hanks and Daryl Hannah, and emboldened Grazer and director Ron Howard to gorge on In-N-Out burgers “with a really good bottle of French Bordeaux.”

A Curious Mind may not turn you into a curiosity evangelist of Grazer-level fervency. But it’s hard to argue with the call to action he sounds in his final chapter, titled “The Golden Age of Curiosity”: “The point isn’t to start asking a bunch of questions, rat-a-tat, like a prosecutor. The point is to gradually shift the culture — of your family, of your workplace — so we’re making it safe to be curious. That’s how we unleash a blossoming of curiosity, and all the benefits that come with it.”

As in wood, Hammer Head reminds us, so in life.

You Might Also Like…

{loadposition YMALND15}